Wola Fabr.

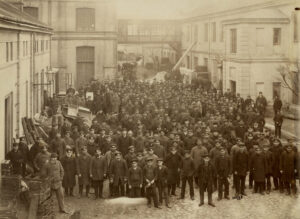

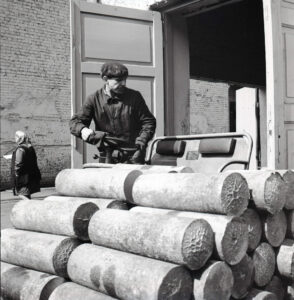

A mural dedicated to the workers of Wola’s industrial plants throughout history.

photo: Jarosław Zuzga

Concept

Historical background

In 1845, the first section of the Warsaw-Vienna Railway was built, a line that was to eventually connect Warsaw with the Prussian partition. Its final unloading stations are located to the west of the city, behind the line of the former Lubomirski trenches. The vast, sparsely developed areas allow for the construction of railway facilities and, consequently, the establishment of many warehouses, workshops and factories around them.

The Ulrych family move into the area and establish a horticultural farm. The “Haberbusch and Schiele” brewery is established and becomes the largest beer producer in the Russian partition. The Warsaw Gasworks is built. A large factory is built by the “Lilpop, Rau and Loewenstein” company, the Norblin, Buch Brothers and T. Werner factories are developing. Investors are mainly entrepreneurs of foreign origin, Germans, Dutch, French, Scots. Their families are rapidly polonising.

The dynamic industrial development slows down with the outbreak of the First World War. The Russians, fleeing from the Germans, take away some of the factories’ equipment and even their crews. They also often destroy what remains.

In 1916, the villages of Wola, Czyste and Koło are incorporated into the Warsaw area, creating a fully-fledged urban district. Railway facilities are developed and, as a consequence, Wola’s industry gains momentum. The factories need manpower, so there is an increase in the number of inhabitants – workers – in the district. In “Lilpop” railway carriages, trams, water turbines, cars, trucks and buses are produced. “Franaszek” at Wolska produces photographic plates and papers. “Polskie Zakłady Philips” starts with light bulbs and soon expands to a manufacturer of electrical appliances, including radios. “Dobrolin” is awarded the Grand Prix at the International Exhibition of Industry in Paris for its shoe polish. “Ursus” at Skierniewicka develops the prototype of the first Polish tractor. The “State Rifle Factory” is launched at Dworska Street. By the outbreak of World War II , more than 800 industrial plants are operating in Wola, tens of thousands of workers are employed in them.

In 1939 the war begins. The Germans are attacking from the west, i.e. through Wola. The owner of the “Dobrolin” factory rolls out barrels of flammable liquid against them, which stops the aggressors for a while. Many of Wola’s factories burn after the bombardments.

After the capitulation of Warsaw, Wola’s industry comes under German administration and from then on it operates mainly to meet the needs of the Wehrmacht. In many factories and smaller plants diversionary activities take place – weapons are produced, documents are forged, railwaymen sabotage transport. In the warehouses of “Ulrych” weapons are collected for the planned uprising, but the Germans seize them even before the uprising breaks out.

During the uprising, some of the factory halls serve as temporary shelters for the Varsovians. In others mass executions of Wola inhabitants take place. The Germans, knowing about the Red Army approaching from the east, destroy most of the factories, and remove their equipment to the west whenever possible. The crews of the Wola factories evacuate on their own. The contents of the Haberbusch and Schiele brewery warehouses save civilians and fighting insurgents from starvation.

The year 1945 brings the liberation of Warsaw. The city is a sea of ruins, with an estimated 90% of the industrial buildings lying in ruins. In spite of this, the inhabitants returning to the capital are trying to start life anew, rebuilding their houses and resuming production in the surviving halls. Soon the Warsaw Gasworks is up and running, the “Wola” electrical substation on Wschowska Street is up and running again. In the late 1940s, Norblin’s crew begins a spontaneous rebuilding of the factory and resumes production.

A new political reality is dawning. The communist authorities need nationalised industry. The so-called “Bierut Decree” comes into force, allowing the city to take over plots of land for the construction of factories. Some of them are built on the ruins of their predecessors, such as the “Rosa Luxemburg Factory” in the place of “Philips”, “Foton” in the Franaszek factory, “Industrial Equipment Building Plant” (later “Waryński”) on the site of “Warszawska Spółka Akcyjna Budowy Parowozów”. The site of the “State Rifle Factory” is occupied by the “Precision Products Factory”, named after Gen. Świerczewski since 1947. “Norblin” is nationalised in 1948 and in 1950 changes its name to “Walcownia Metali Warszawa”, “Dobrolin” and “Ulrych” operate under their own names, but under state supervision. Magister Klawy’s nationalised pharmaceutical plant changes into “Polfa-Warszawa”. The great “Lilpop” disappears irretrievably. New large factories are also established, such as “Marcel Nowotko’s Warsaw Mechanical Works” and “Marcin Kasprzak’s Radio Works”.

The 1960s/70s were the golden age of Wola’s industry. Tens of thousands of people worked in the plants, and the whole of Poland was supplied with electronic, technical and construction equipment manufactured in Wola. “Kasprzak” tape recorders conquer the country from the sea to the Tatra Mountains. “Browary Warszawskie” (Warsaw Breweries) buys the licence for Coca-Cola, which in the reality of communist Poland immediately becomes a sales hit. “The House of the Polish Word” prints hundreds of millions of copies of magazines a year. There are thriving cultural units attached to large factories, children of employees go to for summer camps in holiday resorts, factories cooperate with Wola schools and kindergartens, events, concerts and art exhibitions are organised. In “Nowotka” Gustaw Zemła sculpts the famous “Polegli Niepokonani” monument. The factories take care of their employees.

Unfortunately, the prosperity ends in the 1980s. The national economy drags on, the big Wola factories cut production and exports. Inflation rises, wages fall, workers’ strikes begin. Industry is decentralised, various companies are spun off from the factories, workers leave, often deciding to become self-employed. Various workshops, warehouses and wholesalers are set up in many factory halls.

The fall of communism brings an end to Wola as an industrial district. The large factories, for various reasons, are unable to compete with the open market. Slowly but consistently, production is dying out. “Świerczewski”, “Kasprzak”, “Waryński” are closing down. In their place, housing estates, shopping malls and office buildings soon spring up. Some, such as “Nowotko” or “Foton”, stand empty and their plots undeveloped. Others, such as “Browary Warszawskie” and “Norblin” are being transformed into multifunctional spaces, preserving and adapting post-industrial buildings. Soon, there is only one large operating factory left in Wola – “Polfa-Warszawa” on Karolkowa, but this too finally ends in 2023, becoming a symbol of the end of Wola as an industrial district.

Wola today?

Today, Wola is becoming an office and residential district and is developing dynamically, thanks in part to the second metro line. New residents are often unaware of the district’s post-industrial character, despite the existence of places such as the Norblin Factory and the Warsaw Breweries. Wola is also still home to many former employees of Wola’s industry, whose contribution to the history of the place is invaluable. It is to them that I would like to dedicate the “Wola Fabr.” mural, and I hope that for both of them it will become a valuable element of the image of today’s Wola and a reason to be proud of its rich history.

photo: Jarosław Zuzga

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Norblin Factory Museum team for taking the mural under their roof and helping with all the organisation.

To Ideamo company for the fantastic realisation of the mural on the wall in Żelazna Street.

To Marta Domagala, Janusz Dziano and Paweł Starewicz for valuable discussions about Wola’s history.

Michał Krasucki for writing the book “Warszawskie dziedzictwo postindustrialne”, to which I keep coming back.

Joanna Rutkowska from Wola City Hall for all her support.

To my wife and daughter – for everything.

Jarosław Zuzga, Warsaw 2025 r.

photos from the Werner family collection and eastnews.pl

Today’s Warsaw Wola is no longer an industrial district, but a modern multifunctional space. Nor is it an outlying district, as it used to be – today, together with Śródmieście, Ochota, Żoliborz and Mokotów, it forms the left-bank centre of Warsaw. However, there are fewer and fewer traces of the former factory life. Smaller and larger industrial plants have disappeared – in fact, only the Norblin Factory and the Warsaw Gasworks have survived. Here and there, architectural “outposts” can still be found, such as Browary Warszawskie (Warsaw Breweries) on Grzybowska Street – almost symbolic traces of the industrial past of this part of the city.

However, the memory of the workers and industrial Wola is still alive – it is nurtured by the Museum of the Warsaw Gasworks, the Wola Museum (a branch of the Museum of Warsaw), and our own Norblin Factory Museum, among others. What’s more, even the building of the Warsaw Uprising Museum is a former industrial site – a tramway power station and later a heating plant, where one of the seven original steam boilers has been preserved to this day.

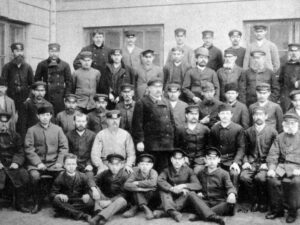

At the heart of this industrial history are the people – the workers of the former factories, without whom there would be neither progress nor transformation.

The Norblin Factory employed up to 2,000 people in the peak pre-war years. Initially, they were mainly skilled metal workers – the elite of Warsaw’s proletariat. Over the years, terminators, craftsmen, seasonal workers and women doing assembly and packaging work joined the team.

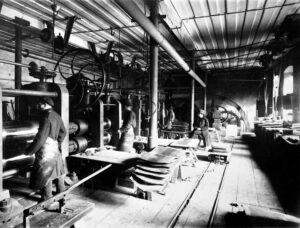

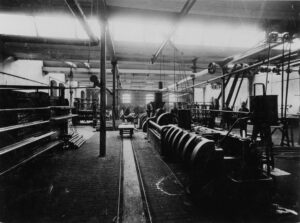

The factory employed, among others, engravers, chiselers, bronzers, turners, rollers, gisers or grinders. There were departments for the production of pipes, wires, electroplating and many other specialities. Social amenities were available for the workers – a factory day care centre, an infirmary, a library, savings funds or the opportunity to buy factory products at preferential prices.

It was not only a job, but also an opportunity for social advancement – many of the employees came from peasant families, craftsmen or impoverished nobility. For them, the former Norblin factory was a place of apprenticeship, stability and professional development. Today, in the modern version of the Factory, the history of people and industry is still present – in the walls, exhibits and stories that remind us that every great change begins with the daily work of many hands.

Artur Setniewski, Director of Norblin Factory Museum

The Singing Steelworker

Discover the history of the place told in the voice of a man who for years co-created its everyday life. Stefan Wieliński – a former metallurgist at the “Warszawa” Metal Rolling Mill – in his personal, moving memoirs recalls the times of hard work at the factory, the people with whom he shared that time and the unique atmosphere of the plant. He himself describes the years spent at Żelazna 51/53 as “the most beautiful in his life”.

This unique recording is a fragment of the living history of Norblin Factory, encapsulated in the voice of its former employee.